The Karakoram Xtreme triathlon represents one of the most challenging and spectacular events of its kind anywhere in the world. It begins with a frigid, high-altitude 1.5 km swim in the glacial Attabad Lake, followed by a 180 km ride along the treacherous Karakoram Highway, and culminates in a full marathon run that crests two mountains. Blending cultural exploration with geographical immersion, the race pushes participants to the absolute limit and beyond.

An enduring legend on the Silk Road, the Karakoram Highway forms the backbone

of the cycling leg. Winding through deep canyons and up steep climbs in the shadow of mountain giants like Nanga Parbat and K2, riders face high speeds, low oxygen levels, and the ever-present threat of landslides. To learn what it’s like to compete in such an unforgiving environment, we caught up with fizik athlete and this year’s only solo full-distance finisher Willy Lin, who takes us through each incredible stage below.

The swim was held at Attabad Lake, situated at an altitude of around 2,600 meters. It’s a dammed lake formed in 2010 when a massive landslide blocked the Hunza River. The water comes from glacial melt in the Karakoram range, where K2 is located. The race guide stated the water temperature would be around 7°C, but because those few days were unusually hot (my bike computer

showed 38°C), the increased melt brought the water temperature down to 5°C.

During the practice swim the day before, I wore not only a wetsuit but also neoprene gloves, booties, a hood, and an extra thermal vest. My core actually felt similar to when I swam in Lake Livigno, but my head couldn’t handle it at all. The parts of my face and ears touching the water were painfully frozen, and after less than three minutes underwater, I had a splitting headache.

"Combined with the high-altitude breathing, every breath felt like a fight for survival, it was the first time in my life that a race felt genuinely life-threatening."

The organizers suggested shortening the swim to 1,000 meters on race day. I had already planned to smear Vaseline all over my face and, if things got too bad, just keep my head above water and breaststroke to the end.

The next morning, I gathered my emotions

and headed toward the swim start.

Because the shoreline was filled with silt, we were supposed to take a dinghy out to the middle of the lake, jump off, and swim back to shore. But the boat operators never showed up, so the organizers suddenly changed the segment to an 8 km run.

Honestly, I felt like I’m rescued.

I took off my wetsuit, changed into my tri suit and running shoes, warmed up, and got ready to start. My plan was to ease into it and let my body acclimate to the altitude. It was indeed extremely hard to breathe, but the high-altitude training I did at Wuling in Taiwan two weeks earlier paid off, my body was able to handle the elevated heart rate. I settled into a steady rhythm and finished the first segment at 5:19/km before getting on the bike.

I fought to suppress the inner thrill that threatened to boil over. The original race briefing had described a 180 km segment with 1,000 meters of elevation gain.

However, the first 40 km immediately threw down the gauntlet with a staggering 700 meters of vertical climbing, a shock that instantly pumped the brakes on my initial euphoria.

The course then transitioned into an incessant sequence of rolling hills. The combination of precarious, exposed mountain slopes (lacking proper soil retention) and the constant low-oxygen hunger in my lungs meant I dared not let my guard down for a single moment.

After steadily overhauling several competitors, I found myself riding largely in solitude, tracing the faint outline of the ancient Silk Road.

To cycle here, on the Karakoram Highway, was an experience so epic it validated every single painful pedal stroke. While the terrain suitable for filming was well-paved, the majority of the route was a treacherous hybrid of asphalt and loose gravel, demanding extreme caution on descents to avoid skidding.

Mid-ride, the course was abruptly shortened due to a major landslide ahead. During the return, while taking a corner descent at 60 km/h, I heard a definitive "BANG."

In that instant, my body prepared itself for the inevitable impact and a hard fall.

Miraculously, by feathering the brakes with precision, I managed to slow down and stop safely. The culprit: a sharp rock had sliced straight through the sidewall of my tire,

and sealant was spurting out uncontrollably.

Thank goodness, the support team was close behind. They quickly replaced the damaged wheel with a spare, and I was soon back on the road.

The magnificent scenery, punctuated by my gasping breaths, was truly stunning. I have ridden through the Alps in Italy, Switzerland, Austria, and France, and across the plateaus of Norway, but the Karakoram offered something entirely different; a raw, wild, and untamed atmosphere. At one point, the experience verged on the surreal: a motorcyclist passed me with an AK47 slung across his back.

Before reaching the transition zone at Ganish Bridge, I had to navigate one or two final tunnels, each stretching nearly 2 km. Inside, it was absolute blackness. My small bike light was utterly inadequate. The psychological torment of blinding oncoming headlights roaring past was deeply unnerving.

In the end, while the planned distance was cut short by 35 km, the total elevation gains still clocked in at nearly 1,800 meters. I completed this magnificent challenge with

an average speed of 29 km/h.

After changing my shoes and doing some quick stretching and refueling, I headed out again. The moment I started with intense UV exposure, the temperature felt close to 30°C.

The altitude training I did earlier paid off again, despite the high heart rate in the thin air, my body could still handle it, and surprisingly, I was even able to run the early

uphill sections.

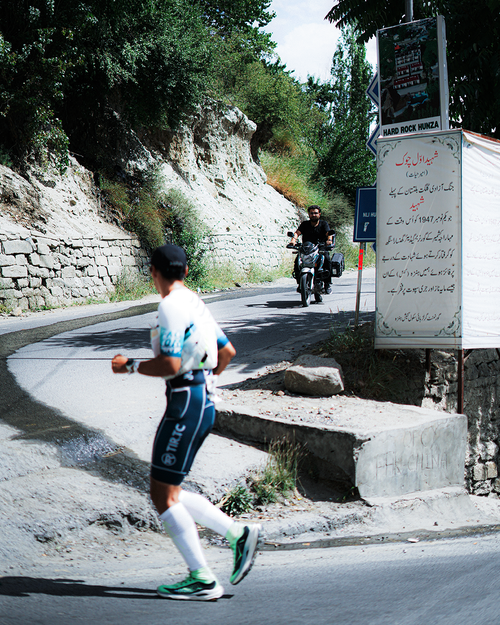

Crossing the Ganish Bridge near the transition area and following the main road, the first big climb began: a 10 km ascent gaining over 700 meters, up to around 2,800 meters at Eagle’s Nest. Dust was flying everywhere; throughout the entire race I felt fine sand between my teeth, and whenever local trucks passed by, it felt like a recipe for instant pneumonia.

After turning onto a smaller access road, the pavement disappeared entirely. The winding trail stretched for several kilometers, sometimes extremely steep, with very few spots to rest or take in nutrition.

Every break required wiping my face, reapplying sunscreen and lip balm. Running and walking in turns, I finally reached the café at Eagle’s Nest, where I ordered lemon juice and a lassi. (I must have been heat-drunk, who orders this salty-soy-milk-like combo during a race?)

After finishing the drinks, I had to run all the way back to T2 and continue toward the next glacier point

Along the way, I replied to the locals’ basic English greetings: "How are you?” “I’m fine, thank you, and you?” and their curious and innocent eyes reminded me of how fortunate I really am.

Of course, not everything went smoothly; I was too lazy to check my GPS and asked a teenager for directions, and he sent me the wrong way; I ended up running an extra 3 km.

By the time I reached the next glacier section, it was near dusk. To get to Hopper Glacier, I first had to run 5 km across a riverbed, with muddy water rolling beside me. It honestly felt like crossing a mythical river to the underworld. The temperature difference between shade and sun was more than 5°C, constantly shifting from hot to cold.

Half dragging myself, I reached the next massive climb, an 11 km ascent gaining over 1,000 meters toward the 3,000-meter K2 and Hopper Glacier viewpoint.

Along the way I passed a few simple, remote villages, losing count of the cows, sheep, and chickens I saw. Having Hendrix, my support crew, join me for part of the run made the journey much more bearable.

Still, I didn’t manage to reach the glacier

before nightfall. What surprised me most was that, just before the finish, there was yet another village, living without electricity, relying on candles and flashlights. I greeted them casually as I passed, chatting here and there, while the air faintly smelled… like cannabis?

I had already been amazed by the scenery all day, but the true reward was at the finish.

The moonlight shone on the snow-tipped peaks, reflecting softly on the glacier and the millions-year-old rocks. How many races in the world end in a place like this?

"And I was the only solo full-distance finisher in 2025."